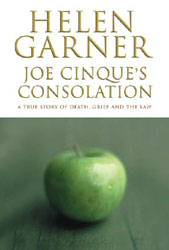

Joe Cinque’s Consolation

Helen Garner, 2004, Pan Macmillan, Australia

June 2009

“I can’t promise to write the book you want, Mrs Cinque’, I said. ‘I’d have to listen to both sides. I would never want to do anything that made you suffer more – but I can’t promise not to – because whatever anyone writes will hurt you.”

Helen Garner, Joe Cinque’s Consolation

On Sunday 26 October 1997, Joe Cinque died from an overdose of Rohypnol and heroin. He died in the bedroom of his inner-suburban Canberra townhouse, after a dinner party where his girlfriend, Anu Singh, had told her friends she was planning to kill herself. Singh was convicted of his manslaughter, and her friend, Madhavi Rao, was found not guilty of any charges relating to his death. When Helen Garner’s book

Joe Cinque’s Consolation was released in 2004, Singh was on parole, Rao was living overseas under a new name and Cinque was still dead.

“Joe Cinque is dead” is the mantra guiding Garner and her reader through her book. After five years of research and deliberation, Garner wrote her story, describing the trials and the characters with a personal narrative that reflects on the case, the law, her involvement with the families and her ongoing dilemma about whether to write and what to write about.

Intertwined amongst the facts and the dramatisations are glimpses of Garner’s life, including her recent divorce, her new flat in Sydney, her demented mother, her taxi drivers and even the affront to her ego when Dr Singh (Anu’s father) dared to suggest that he could help pay for the publication of a book.

Garner positions herself as a “normal” person reflecting on the nature of the legal system, and it is this position that sets the tone of her book and directs the attention and sympathies of the reader.

What is the crime?

Writing an investigative, non-fiction or true crime book gives an author the freedom to approach a story differently from the factual reporting of a print journalist. Generally written after an event, true crime writers tend to have the enviable knowledge of hindsight, a full public record and the personal accounts of those involved.

With the “whodunit” question usually already answered, author’s try to answer a “why” - why they “dunit” or why the system failed. Garner was unable to answer why Singh killed Cinque or why no one stopped her, so she questioned the legal system and the nature of justice.

The assumption of innocence?

The Australian legal system is built on the assumption of innocence. Australian arrestees “have the right to remain silent”, with the burden of proof on the prosecution to establish guilt. Singh and Rao did not have to prove their innocence, so and neither spoke at their trials, denying reporters, spectators and Garner their voices or perspectives.

The cases were tried in the ACT, which allows the defense the choice of a jury or judge trial. Singh and Rao’s defense teams chose a judge over the emotional decision of a jury. As Justice Ken Crispin made his decisions based on the evidence presented, Garner questions the laws of evidence, such as why the prosecutor’s psychiatrists could not examine Singh, but her defense team had full access and therefore able to present more credible evidence. The answer remains that Australian courts assume innocence, but the emotions of a grieving family blur its clarity.

Garner’s “fantasy of journalistic even-handedness” gave way when the system supported the silence of the defendants and when Singh and Rao maintained their rightful silence by denying Garner’s interview requests. At this point, Garner describes her decision not to write the book and lets the reader believe that her decision was overturned by a meeting with Maria Cinque (Joe’s mother) and what, may have, started as a true crime reportage book, became a quest, as Garner told The

7.30 Report in 2004, to “restore some dignity to Joe Cinque”.

Getting to know Joe?

Joe Cinque’s Consolation is about Joe Cinque. He is described by his family and friends as a loving, devoted and loyal, and Garner never appears to seek any alternative opinions.

The same rose-coloured glasses are not applied to Garner’s portrait of Singh. Garner describes her first impressions of Joe and Anu from a photo in a newspaper.

“He held his chin up with a shy, almost defensive smile, while the girl in his embrace turned her head to beam into the camera with the ease of someone accustomed to being adored and to looking good in photos…Anu Singh raised my girl-hackles in a bristle. Joe Cinque provoked a blur of warmth… These were my instinctive responses, and over the ensuing years, as I hacked a path through this terrible storm they remained remarkable stable.”

This photo was printed in a newspaper and easily found on the internet, but is not reproduced in the book. With the exception of a small black and white picture of Joe, there are no photos in Garner’s book (which is unusual for true crime), which leaves the reader with little choice, but to accept Garner’s descriptions and interpretations.

Getting to know Anu?

Family and friends recount Joe, but there is no corresponding portrait by people who love Anu. She is described by her appearance on the security tape after her arrest and as a woman wearing high heels and adjusting her hair at her trial.

Garner’s descriptions of Singh and the dramatisations of the events leading to Cinque’s death leave a negative, almost stereotypical, picture of a cold, manipulative, irrational woman – a character designed to raise a reader’s “girl-hackles”.

Singh’s verdict and sentencing were based on a defense of diminished responsibility due to psychological illness, but Garner gently dismisses the medical evidence by joking with the “young journalists” covering the trial that eating disorders and paranoia are normal for 20-somethings. She reports the medical evidence, but never lets the reader get close enough to explore or understand it.

She distances and distracts the reader further by comparing her own adolescent choices (her manipulation of men and her decision to hide an abortion from her parents) to Singh’s behaviour. This cleverly leads the reader to compare their own life choices to Singh’s and search for a time when they behaved irrationally. Garner assumes that her readers cannot see themselves taking a life.

Hearing Anu?

On the release of the book in 2004, Anu Singh was also very aware that her voice is missing from the account and was interviewed, in her parent’s home, by Phillip Adams for

ABC radio’s Late Night Live.

Adams shares with Singh that her character in the book is “terrifying” and that “Lady Macbeth comes off better”. Singh admits that she can see herself in Garner’s “unfortunate”, description, but it’s “very exaggerated … because she hasn’t spoken to me and she decided on what I was like by a photo”.

Singh insists that she would have been happy to talk to Garner, but that her request (documented in the book) came at a time when she was physically and mentally unable, and wishes that Garner had asked her again.

Singh’s real voice in the radio interview is quite different from her dramatised voice in the book. Her Australian accent doesn’t place her as Indian (a fact regularly discussed by Garner) and she speaks with a rationality and calmness denied her semi-fictional self. Adams’s interview continues to seek the same answer denied to Garner and he asks Singh why she killed Joe Cinque. Singh answers:

“There’s absolutely no legitimate or rational motivation at all. And the few days prior to that, my memories of it, is still a little bit hazy and the details are sketchy. But, I can’t. It’s terrible being in a state of mental health wellbeing, and trying to put myself back there, and determine what was going on and what I was thinking.”

Singh gives the same answer put forward by her defense seven years earlier.

Would Maria kill Anu?

Adams also interviewed Joe’s parents, Maria and Nino Cinque. After watching them at the trials and sitting in their Newcastle home with Garner, the Cinques’s voices are recognized like old friends. They tell Adams that they are “very happy” with Garner’s book and the story they share with Adams is almost exactly that which Garner reports.

They are naturally still in pain, they still want justice and do not believe that Singh was “sick”. Singh told Adams that she was interested in pursuing a program of restorative justice and he brought a message to the Cinques:

Phillip Adams: Well as I said, I bring you a message from Anu, who extends to you her profound regrets and wants to in fact involve you, if it were possible, in a restorative justice program, and your answer is No?

Maria Cinque: No way, no. She can rot in hell, forever. She said she was going to kill herself, what she is waiting for?I

In Garner’s book, Garner records Maria Cinque’s declarations that she would run over Anu Singh if she saw her on the street and wishes Singh would follow through with her talk of suicide.

Much of the book questions the inaction of Singh and Cinque’s friends as Singh talked about Joe’s death. The case attracted so much attention because “farewell” dinners held at Singh and Cinque’s house. She had often talked of suicide and even discussed taking Joe with her, but none of the friends in contact with Singh over that week did anything to stop her, even when it was known that she had injected her partner with heroin.

Rao was the only friend charged, while others were called as witnesses. Again, Garner dismisses the process of the law that deemed these friends and acquaintances free from responsibility or legal guilt. She dramatised conversations and events leading up to the death, based on the evidence presented in the courts, rather than reporting the facts third hand, bringing the reader as close as possible to the situation where these young people appear incapable of doing the right thing.

The friend characters are young, intelligent law students, studying at Australia’s national university, and some involved are practicing professionals today. Garner is appalled by the “gross fact” that women trade sex for drugs and draws attention the homeless, “junkies” wandering Canberra’s Garema place. Her description of drug users is hopeless, mindless and wasted people, and she does not appear to believe that a heroin user can be a middle class, active member of our society – let alone an intelligent student.

Drugs were a part of Singh’s university and social culture. No one involved seemed shocked or concerned about Singh’s drug use or her talk of suicide, as it wasn’t considered unusual. Singh herself said she was surprised at how many people talked about suicide with her.

Viewed from a point after the death of Cinque, it is easy to see when and how people could have stepped in and possibly prevented his death, but according to the evidence, no one believed that Singh was ever going to act, seeing her erratic behaviour as a result of her eating disorder and her drug use.

Clearly Garner believes that Maria Cinque had no real intention of running over Anu Singh, as this conversation is reported as a poignant reminder of the mother’s grief. Garner doesn’t stop Maria Cinque from driving a car, as no one stopped Anu Singh.

Conclusion

Despite the legally conclusive results of Anu Singh and Madhavi Rao’s trials, Helen Garner does not know why Joe Cinque died and wants her readers to question the justice received by his family.

Singh’s right to remain silent and her decision to remain silent leave little room for Garner to present an opinion that could see her positively or even with empathy or understanding, and Rao is discussed as someone totally in Singh’s control. Even without their active participation, there was evidence and opinion that could have led Garner to different conclusions, but it is doubtful that alternative conclusions would have pleased the Cinques.

The writer’s journey through

Joe Cinque’s Consolation vividly describes the Cinques’s grief and the senseless nature of Joe’s death, and she joins his family in their anger towards the legal system and their belief that justice has not been served. Her personal reflections and observations bring the reader intimately into her personal experience and ensure that the appealing and loving Joe Cinque will not be forgotten by anyone who reads the book.

Review of

Criminology, a play based on the same case.